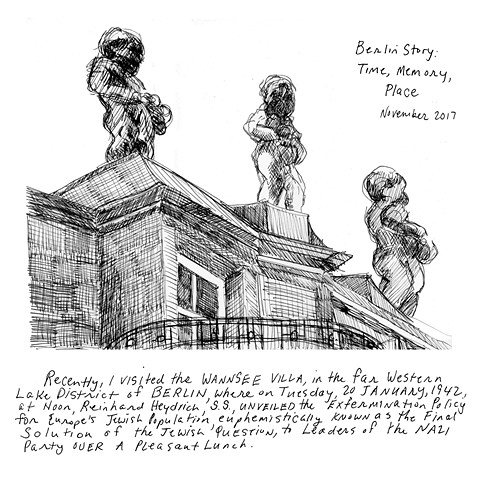

Berlin Story: Time, Memory, Place

Berlin Story: Time, Memory, Place, a story about a visit to a beautiful villa, juxtaposes the calm elegance of the architecture with the horror that happened within. Cleaver Magazine, 2017

Like fresh snow covering over a messy urban landscape, there’s a kind of concealing but also unifying quality to the fourteen central images of Emily Steinberg’s “Berlin Story.” Following a four-panel introduction, in which our narrator introduces herself as having grown up an anxious, fearful depressive, lost in the grip of, among other things, the “images of death, murder and gratuitous Nazi sadism” shown to her in Hebrew school, we are presented with still portrayals of an uninhabited, idyllic setting.

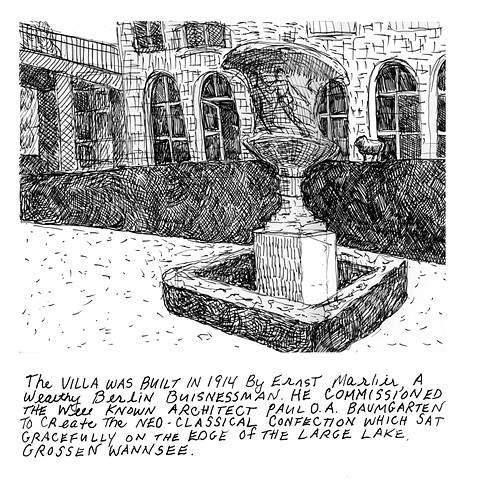

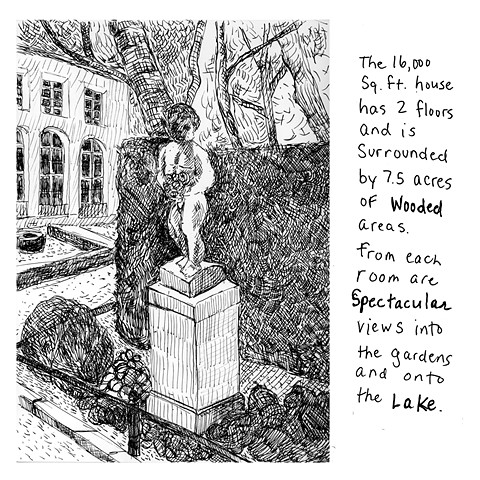

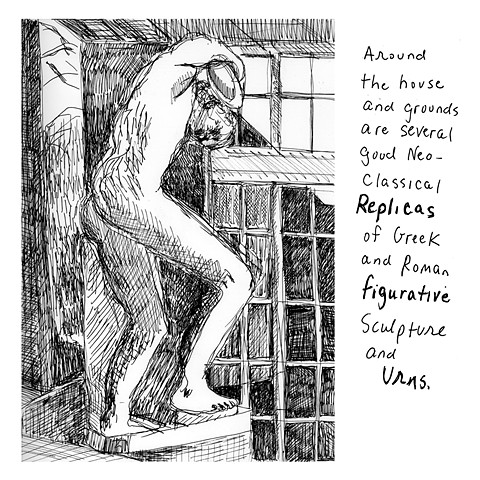

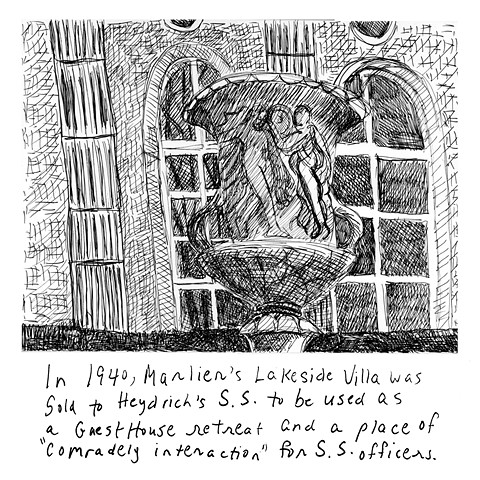

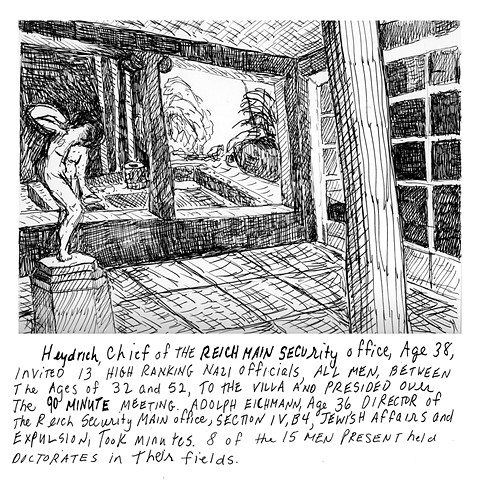

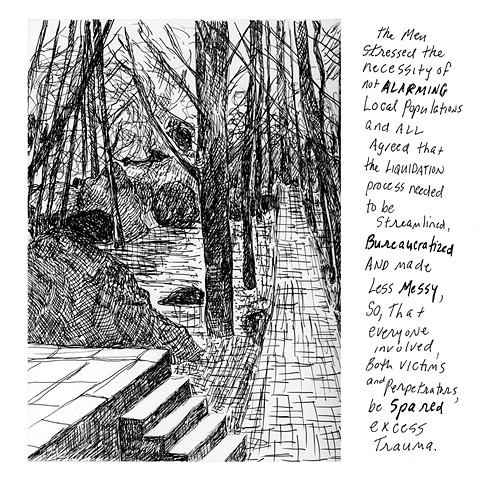

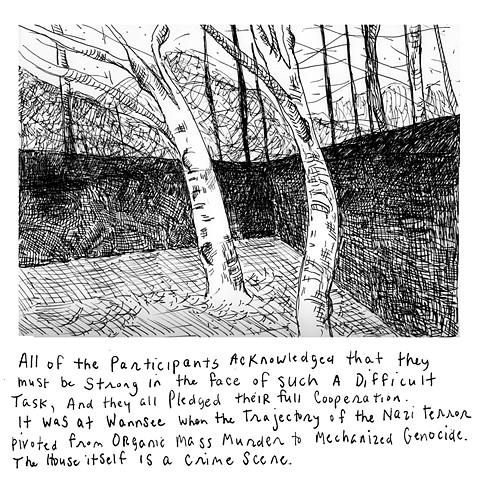

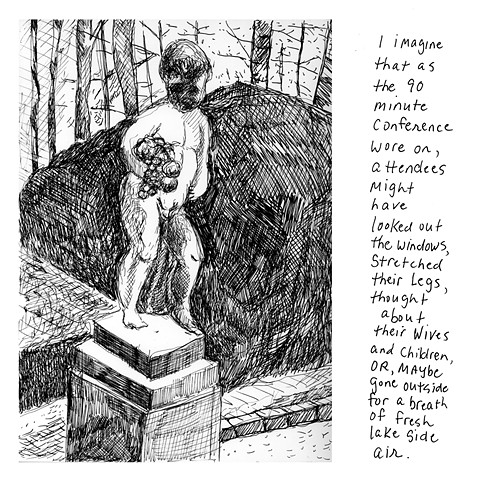

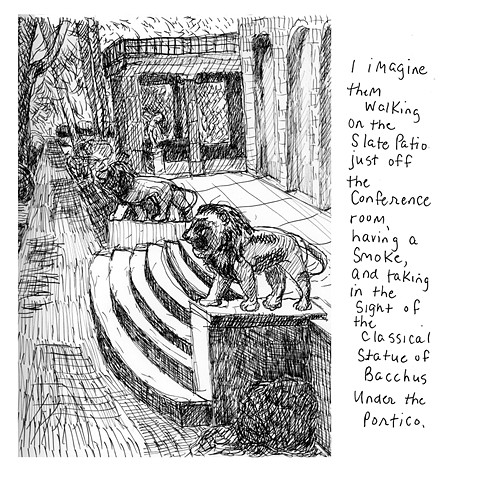

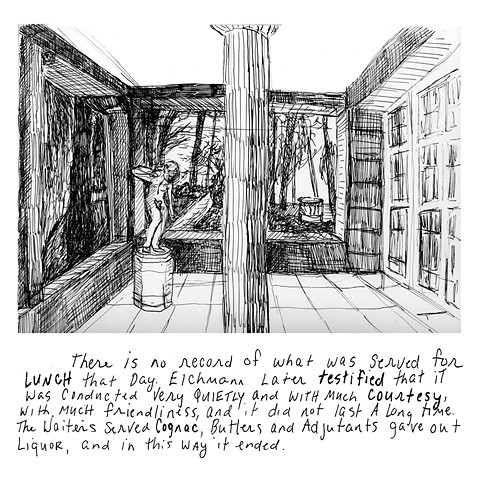

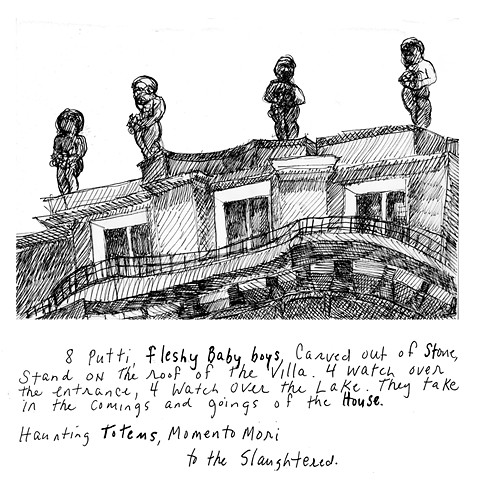

Each drawing, contained in an unframed rectangle, presents its viewers with a narrowed angle, or point of view, proximate to or regarding the famous Wannsee Villa, a mansion located in the suburbs of Berlin. The drawings are in black and white, cramped with details composed from demarcated lines, some of them even slightly wobbly marks. From four cherubs adorning the villa’s rooftops to two tree trunks gracefully tilting somewhere in the vicinity of the house grounds, we glimpse this locale as either a deliberately or unintentionally naive visitor might; this is a structure embodying decadence and wealth, good taste and fine craftsmanship. Here is a sculpture to admire, swaddled in a bouquet of well-groomed foliage. Here is a fine urn, hefty, ornamented, inviting contemplation. We walk its grounds, invited to by our guide. We revel in its beauty.

The handwritten dispatches, scrawled sometimes beneath and sometimes beside these postcard pictures, interrupt our reverie. “On Tuesday, 20 January 1942 at noon, Reinhard Heydrich, S.S., unveiled the extermination policy for Europe’s Jewish population, euphemistically known as the Final Solution of the Jewish Question, to leaders of the Nazi Party, over a pleasant lunch.”

What’s startling is that with these words, the images don’t suddenly transform; no visible traces of that exchange, or its consequences, are apparent in the pictures here, even in the intimate and exhaustively rendered tiny lines, the single- and cross-hatches of our once-depressive guide, who has “never completely” let go of those horrifying images presented to her in her youth, part of her Jewish heritage. The words tell us not only, or simply, of the terribleness, but instead fill us in on details presumably meant to help us picture what is, in fact, impossible to conjure up. Thirteen men, officials, ranging from thirty-two to fifty-two years old, gathered for a ninety-minute meeting dedicated, in part, to discussing the eradication of Jews. A thirty-six year-old Adolph Eichmann was charged with taking minutes. “There is no record of what was served for lunch that day,” another narrative accompaniment tells us. “The waiters served cognac, butlers and adjutants gave out liquor.” Ultimately, neither images nor words, here or elsewhere, can fully convey to us what took place, can help us imagine what is unimaginable.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the conference, the Wannsee Villa was finally made into an educational and memorial site. Another quarter of a century has now passed. Still, none of this history seems teachable, transmittable. Steinberg’s sequence reveals how, despite all efforts to the contrary, despite all inclinations to conceal, the horror nonetheless lives on.

Tahneer Oksman,

Assistant Professor and Director of the Academic Writing Program Marymount Manhattan College